WHO'S IN A NAME?

People Commemorated in Eastern Sierra Plant Names

Return to Index

Cliffbush, Jamesia americana Torr. & A. Gray (Philadelphaceae)

by Larry Blakely

References and Notes

(First Posted: 2000 03 05; Last Revised: 2000 03 27; Text appeared in the newsletter of the Bristlecone chapter, CNPS, March, 2000/Vol. 20, No.2)

Cliffbush, Jamesia americana Torr. & A. Gray var. rosea C. Schneider

Check the CalFlora website for more information and pictures.

Photos © by Larry Blakely

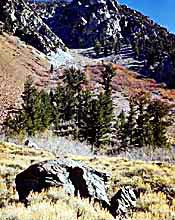

You're at about 10,000 ft. in the Eastern Sierra when you come around a bend in the trail and there, adorning a fissure in a granite wall, is a diminutive shrub bedecked with rose-tinged white flowers much like those of an orange tree. Its leaves are small, rounded, fuzzy, serrate, and prominently veined. You have encountered cliffbush, first discovered in 1820 in the Rocky Mountains by a botanical pinch hitter, who hit a one-time-only grand slam home run.

Edwin James (1797 - 1861) (1) (2) (3), (4) the hero of this essay, was born and raised in Vermont. He trained in medicine and studied botany, the latter, most notably, with John Torrey. But his star quickly faded from botanical notice after his one great year of solid accomplishment. And the cheerful aspect of the cliffbush, which must have given James much joy when he discovered it (along with so many other Rocky Mountain plants in full July glory), was apparently not reflected in the discoverer's later years.

Edwin James, in possibly his only photo, reproduced in Ewan's Rocky Mountain Naturalists (1).

C. C. Parry said "Dr. James was tall, erect, with a benevolent expression of countenance, and a piercing black eye." (1) Parry was the next botanist, after James, to climb Pike's Peak, in 1862.(5)

James was botanist, geologist, and chronicler on the second season of the 1819/1820 US Army expedition led by Major Stephen Long. William Baldwin, a well-regarded US botanist but a person of chronic ill health, was selected as the expedition's botanist and served well during the first season. Unfortunately, he died in Missouri near the end of that season. A replacement was needed, and, upon recommendation of Torrey and others, James, at age 23, got the job.

Long returned from the east, with fresh orders as well as with James, to the winter encampment of the small expedition on the Missouri River, near present day Omaha, NB. The purpose of the expedition now, much reduced from original plans, was to search for the sources, in the Rocky Mountains, of the Platte, Arkansas, and Red Rivers, and to gather scientific data along the way. Before setting out they were assured by Indians and Whites alike that they could not possibly survive such a trip, that they would succumb, if not to hostile Indian bands, then to the lack of water and animal fodder over much of the way. They were indeed to suffer numerous hardships, but survive they did.

Pike's Peak (7)

Soon after reaching the base of the Rockies, James, with two other men, set out to climb a high peak described, but not climbed, by Zebulon Pike in 1806 (Pike had considered it impossible to climb, and so had others later). Nevertheless, carrying 10 lbs. of buffalo meat, 2 cups of corn flour, a small kettle, and a light blanket each (6), these men succeeded in reaching the top, the first Whites to climb an American peak over 14,000 ft in elevation. The excursion took only 3 days. On the second day they needed to hurry to get to the peak's top and back down to a more hospitable altitude before dark, but "... we met, as we proceeded such numbers of unknown and interesting plants, as to occasion much delay . . ." James became the first to collect many new alpine plant species, which were then in riotous bloom. Major Long named the mountain James' Peak, but later the name Pike's Peak came to be accepted.

Pinus flexilis James.

Webber photo (©)

James returned to the East with some hundreds of new plant species. In addition to cliffbush, there were others which also occur in our area, including limber pine (Pinus flexilis James), mountain maple (Acer glabrum Torrey), narrow-leaved cottonwood (Populus angustifolia James), and streamside bluebells [Mertensia ciliata (Torrey) G. Don]. The expedition's zoologist, Thomas Say, discovered a number of new bird species which also grace our region, including Say's Phoebe [leaving no doubt about who it's named for, its scientific name is Sayornis saya (Bonaparte)].

Most of James' plants were named by Torrey. James named only a few, then turned his collections over to Torrey when he thought he would be going along on a second expedition led by Long, this time to the head waters of the Mississippi. (It's a bit strange that he wanted to go on Long's second expedition, considering that he had greatly disapproved of Long's leadership on the first. (3)) But somehow he missed connections and was left behind.

Mertensia ciliata (Torrey) G. Don.

Brousseau photo (©)

Surprisingly, considering his obvious talents, James made no further marks on botanical science. He served as a surgeon in the US Army for a few years (during which time he studied Indian languages), later edited a temperance journal, and, in 1836, moved to Iowa, where he lived out his years. He died at age 64 of injuries sustained in a wood hauling accident.

With his move to Iowa, his "... peculiar traits ... became more conspicuous. His mode of life, his opinions, and his views on moral and religious questions generally, were inclined to ultraism ... [though] his errors were on the side of goodness..." "He was a remarkable man in many respects ... a unique character. ... a mystic, a recluse, an abolitionist, ... a non-resistant ... more perhaps like a Tolstoi of to-day." "He has his peculiarities, and the masses cannot appreciate him, he is at least two hundred years ahead of the time in many things ...". (2), (8)

James wrote to Torrey (who had written to ask of his activities in his later years) in 1854: (1) "...I see not much to regret in my course of inaction ... I feel myself approaching the chill and foggy domains of theology, to walk in which ... should be wholly distasteful to a true lover of nature like yourself, John Torrey, ..." ending, with a touch of sad cynicism, "It enters my day dreams that I may yet go forth to gather weeds and stones and rubbish for the use of some who may value such things, and perhaps drop this life-wearied body beside some solitary stream in the wilderness." (8)

REFERENCES and NOTES

- Ewan, Joseph. 1950. Rocky Mountain Naturalists. Univ. Denver Press. pp. 13-20.

- McKelvey, Susan Delano. 1956. Botanical Exploration of the Trans-Mississippi West 1790-1850. 1991 Reprint, Oregon State Univ. Press, Corvallis. pp. 211-249.

- Stroud, Patricia Tyson. 1992. Thomas Say, New World Naturalist. Univ. of Penn. Press, Philadelphia. pp. 108-131.

- Rodgers, Andrew Denny. 1942. John Torrey, A Story of North American botany. Princeton Univ. Press. pp. 47-53.

- Weber, William A. 1997. King of Colorado Botany, Charles Christopher Parry, 1823-1890. Univ. Press of Colorado. Includes Parry's account of his ascent of Pike's Peak, with many references to plants seen 42 years earlier by James.

- James, Edwin. 1823. Account of an Expedition from Pitsburgh to the Rocky Mountains, Performed in the Years 1819 and '20. Two Volumes. Philadelphia. 1966 Reprint, Readex Microprint Corp.

James wrote this Account soon after returning to the East. It was very well received at the time, and remains quite interesting and readable today. Volume II, Ch. II (pp. 23-41), covers the climb of Pike's Peak. - United States IPA Region 17, Colorado and Wyoming, Travel and Recreation, http://www.ipa-usa.org/region17/travel17.htm [broken link]

- More complete (and additional) quotes:

"... peculiar traits... became more conspicuous. His mode of life, his opinions, and his views on moral and religious questions generally, were inclined to ultraism . .. he gradually assumed the habits of a recluse... With him to espouse a cause, was to carry it to the farthest possible extremes, often erroneous . . . at times positively wrong.. it must be admitted that his errors were on the side of goodness ... On the 25th of October, 1861, he fell from a load of wood, the team descending a small pitch of ground ... both wheels passed over his chest ... He lingered ... until the morning of October 28th, when he expired at the age of 64 years ... (Biographical sketch by L. H. Pammel, cited in McKelvey, p. 247.)

"The life of Edwin James is worthy your thorough study. He was a remarkable man in many respects-personal, scientific, historic, moral and religious-a unique character. Personally I only knew him as a mystic, a recluse, an abolitionist, a come-outer, an underground conductor for men 'guilty of a skin not colored like his own,' a non-resistant, in fact a 'John Brown' man, but never to the extent of taking up arms, more perhaps like a Tolstoi of to-day. I could never draw him out on his past life. He would not talk about himself..." (William Salter, cited in McKelvey, p. 247.)

"...Mr. James...was in my office...and in looking over the Plantae Wrightianae he was considerably amused to see that his opinion with regard to the Cacurbita perennis of Gray, he calling it Cucumis perennis was marked doubtful. He still thinks he is right, he told me Dr. Torrey first differed with him. He is as enthusiastic and ardent as ever, and remarked to me that he would walk one hundred miles to see a new plant, but would like to take the steam-boat back. You would have been delighted with him. He has his peculiarities, and the masses cannot apreciate him, he is at least two hundred years ahead of the time in many things..."(From a letter by a friend of James written to C. C. Parry, cited in McKelvey, p. 221, fn. 3.)

"... as this world counts doing: little or nothing. It did not take me long to discover that it was not for me to make my mark upon the age and having settled that point to my own satis-faction I determined to make it on myself. I said 'I will rule my own spirit and thus be greater than he that taketh the city' ... I see not much to regret in my course of inaction and passiveness as to the things of the life that is. . . But I feel myself approaching the chill and foggy domains of theology, to walk in which may and should be wholly distasteful to a true lover of nature like yourself, John Torrey, I will say no more about these things. ... It enters my day dreams that I may yet go forth to gather weeds and stones and rubbish for the use of some who may value such things, and perhaps drop this life-wearied body beside some solitary stream in the wilderness." (Letter to John Torrey, March 3, 1854; cited in Ewan, p 18.)

"... I became a settler in Iowa twenty-two years ago and of course have seen great changes. The locomotive engine and the railroad car scour the plain in place of the wolf and the curlew. Mayweed and dog fennel, stink weed and mullein have taken the place of 'purple flox and the mocassin flower,' the Celt, the Dane, the Swede and the Dutchman are instead of Black Hawk and Wabashaw, Wabouse, Manny-Ozit and their bands..." (In a letter from James to C. C. Parry, February 11, 1859, cited in McKelvey, p. 247.)